John Galen Saylor (1902-1998) was an American educator. He had FulBright professorship for Finland in 1962. He was an authority on curriculum, also supported a program of national assessment.

William Marvin Alexander (1912-1996), another American educator, was known as the “Father of the American middle school” movement. He was also an author of more than 250 books and articles.

Galen Saylor and William Alexander (1974) viewed curriculum as “a plan for providing sets of learning opportunities to achieve broad educational goals and related specific objectives for an identifiable population served by a single school center”.

Saylor-Alexander-Lewis Curriculum Development Model

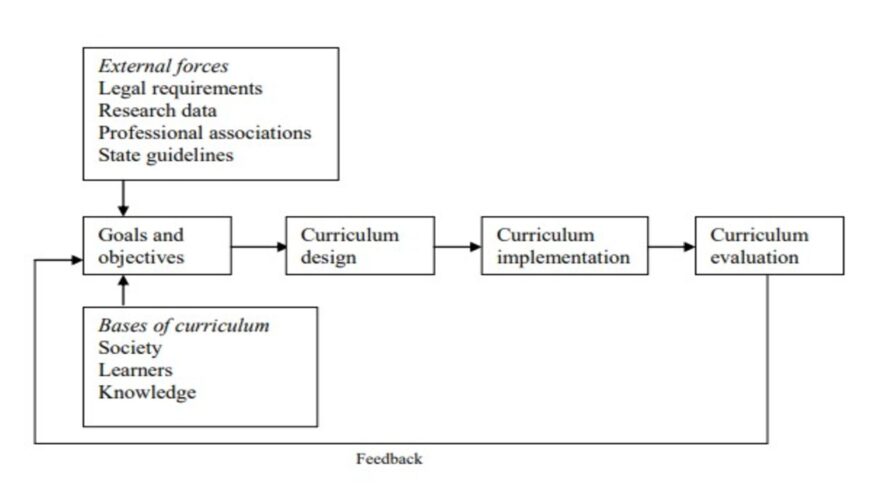

Saylor and his colleagues (1981) used an administrative approach to curriculum development. They discuss and evaluate lesson plans in terms of how ends and means relate to one another, how important facts and figures are paid attention to, and how activities or procedures flow from start to finish. Their conceptual model of the curriculum development process, comprising four stages, is shown as under.

1. Selection of Curriculum Goals and Objectives

According to this model, curriculum designers should start by outlining the main educational objectives they want to achieve. They recommend the use of the following four curriculum domains, with each major goal representing one.

- Personal Development

- Social Competences

- Continued Learning skills

- Specialization

The selection of educational goals and objectives is influenced by

- External forces, including legal requirements, research data, professional associations, and state guidelines, and

- Bases of curriculum, such as society, learners, and knowledge.

Curriculum developers then choose the combinations of curriculum design, implementation strategies, and evaluation procedures that are calculated to maximize the attainment of goals; review feedback from the plan in effect through instruction; and re-plan the elements of the curriculum as indicated by the data.

2. Curriculum Design

Curriculum design involves decisions made by the responsible curriculum planning group(s) for a particular school center and student population. A broad framework, or curriculum design, is created or chosen by curriculum planners for the learning opportunities to be offered to students after they have gathered and analyzed essential data, identified goals, and specified objectives. Among their alternatives is a subject design utilizing specific studies in the specified curriculum area, a scope and sequence plan built around a selection of persistent topics or themes, an analysis of the essential skills necessary for knowledge and competence in the subject area, and a selection of problems (in cooperation with students) related to the area of study. The design plan ultimately anticipates the entire range of learning opportunities for a specified population.

3. Curriculum Implementation

Curriculum implementation involves decisions regarding instruction. Various teaching strategies are included in the curriculum plan so that teachers have options. Instruction is thus the implementation of the curriculum plan. There would be no reason for developing curriculum plans if there was no instruction. Curriculum plans, by their very nature, are efforts to guide and direct the nature and character of learning opportunities in which students participate. All curriculum planning is worthless unless it influences the things that students do in school. Saylor argues that curriculum planners must see instruction and teaching as the summation of their efforts.

4. Curriculum Evaluation

Curriculum evaluation involves the process of evaluating expected learning outcomes and the entire curriculum plan. Saylor and his colleagues recognize both formative and summative evaluation. Formative procedures are the feedback arrangements that enable the curriculum planners to make adjustment and improvements at every stage of the curriculum development process: goals and objectives, curriculum development, and curriculum implementation. The summative evaluation comes at the end of the process and deals with the evaluation of the total curriculum plan. This evaluation becomes feedback for curriculum developers to use in deciding whether to continue, modify, or eliminate the curriculum plan with another student population. The provision for systematic feedback during each step in the curriculum system—and from students in each instructional situation—constitutes a major contribution to Saylor and associates administrative model of curriculum development.

Significance of S-A-L Curriculum Model

Developing curriculum models provide a structure to systematically and transparently map out the rationale for the use of particular teaching, learning and assessment approaches in the classroom and are regarded as an effective and essential framework for successful teachers. Saylor and Alexander curriculum model helps teachers to design their own instructional plans based on the designed curriculum, evaluate and edit if needed. This model works appropriately for each of the domain mentioned above.

The S-A-L model is deductive; it moves from the general (e.g., assessing societal needs) to the particular (e.g., specifying instructional objectives). Additionally, the model is linear; from beginning to conclusion, it follows a specific order or series of stages. However, linear models do not have to be constant sets of actions. The model’s entrance points and interrelationships can be decided upon by curriculum designers. The model is also prescriptive; it makes recommendations for what should be done and what many curriculum designers actually undertake.

In a nutshell, this curriculum model offers substitute modes along with recommendations, fostering adaptability and greater freedom for both teachers and students. It provides students autonomy and establishes them as subject matter experts in what they need to know. Additionally, it respects the learners’ social and cultural backgrounds. However, it could also be challenging for teachers to establish a good balance between students’ needs and interests.

References

Saylor, J. G., & Alexander, W. M. (1974). Planning Curriculum for Schools. Edition 3rd. NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Saylor, J. G., Alexander, W. M., & Lewis, A. J. (1981). Curriculum Planning for Better Teaching and Learning. Edition 4th. NY: Holt-Saunders.

OTHER RELATED POSTS